People who, at the cost of their own health and life, eliminated the consequences of the disaster, are almost forgotten 34 years after the liquidation of the accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. They are forgotten by the state, which determined for them the Chernobyl benefit in the amount of 100–450 hryvnias per month. Sometimes, they even have to get a ticket to the sanatorium with a fight. These people are mostly remembered “by the date”: December 14, the Day of Honoring the liquidators of the consequences of the Chernobyl accident, and April 26, the next anniversary of the explosion at the 4th power unit of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant.

The current “smartphone” youth is sometimes surprised: are there still living liquidators of the consequences of that terrible accident among us? It was so long ago. Fortunately, there are. However, they are scattered throughout the entire post-Soviet space. They went to the Chernobyl nuclear power plant from all over the Soviet Union. According to official statistics, there were at least 526,250 such heroes. Unofficial sources declare a slightly different figure – 600,000. Today there are 193,800 participants in the aftermath of the Chernobyl accident in Ukraine, of which 57,782 are disabled.

Chernobyl is interesting only for true enthusiasts

Unfortunately, it happened that today, the oral stories and memories of the liquidators are mainly interesting for enthusiasts and the Chernobyl victims themselves – members of public organizations. Now, few scientists are involved in the “Chernobyl” topic in Ukraine. In fairness, it is worth saying that 34 years ago, few thoughtfully interested in this issue, including the highest leadership of the republic.

What is the fact that immediately after the Chernobyl accident, the first letter of the Ministry of Health of the Ukrainian SSR addressed to the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, Vladimir Scherbitsky, indicated that the level of radiation of water in the Dnieper River rose a thousand times. Moreover, it was written by hand Shcherbitsky in the margins of the document: “And what does this mean?”

Our leadership was so unprepared for this problem that it didn’t even fully understand what consequences the increased background radiation caused by thousands of times. Now, when the liquidators are getting smaller and smaller every year, it is important to have time to record, study and preserve their life and professional experience for future generations. Basically, this is done only by enthusiasts, ascetics, who are not indifferent to the history of their people – adherents of the idea of a safe ecological heritage.

Ivan Gnatenko is a liquidator of the Chernobyl accident, category 2, reserve major. He shares his memories of the time he spent on liquidating the consequences of the Chernobyl accident, constantly interrupting his story with heavy breathing. Emotions overwhelm the liquidator’s already sore heart. The accident, if it didn’t fundamentally change the life of such people, essentially influenced, first of all, their health, physiological and mental, in general, their moral state.

Ivan Gnatenko talks about his condition after returning from the exclusion zone:

“… I went to work immediately upon returning from the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. At first, it was normal, and then, literally a week later, I began to feel that I was physically, psychologically, morally ill. I could not do anything. I got out with the help of good people. When my second daughter was born in the family, I got another job. Radiation was deposited in my bones: in the knee, elbow joints. At the age of 27, I had no teeth – everything rained down. I went to the mirror and extracted all my teeth, because I no longer held on. I am 27 years old, but I have no teeth. I had to make dentures. And I survived it. If you analyze now, I had a terrible depression then, in 1986: it seemed like I was dying. Thanks to my wife, her words, her support, thanks to my daughter, I survived and live. And so, if they had not supported me, I could have committed suicide. I literally felt like I was dying.”

“The Victim’s Syndrome”

Thus, we can confidently talk about the existence of the so-called Chernobyl syndrome. No one provided psychological assistance to the Chernobyl victims. They found themselves face with their problems and fears. The family and the support of relatives and friends helped to fight for a normal future life.

Back in 2000, the monitoring results were presented to the public at the International Conference “The Medical Consequences of the Chernobyl Disaster: Research Results”, which testified not only to mental disorders in the liquidators of the accident and people who lived in the Chernobyl zone, but also to the specifics of the psyche of these people. Increased anxiety, disappointment in one’s own abilities, the so-called “victim’s syndrome” are characteristic features by which these people can often be identified even today.

It is important to note the sense of responsibility towards the Motherland. Ivan Ivanovich says this:

“… I was taken to the draft board early in the morning. And I had to go to defend Ukraine from the atomic monster. I believe that I have fulfilled my duty to the state and how much God has measured for me, how much I will live. It’s only a pity that our state threw people like me into a landfill, like used material.”

But even now, being a Chernobyl disabled person, he claims that if he had been called again, he would have gone again.

We will judge by the law of wartime for failure to comply with orders

Another liquidator of the accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, Alexander Goncharenko, tells in his memoirs the following facts:

“… Nobody took me by force to Chernobyl. A representative from the military enlistment office came and handed the summons. Then we swore an oath to the Soviet Union. There was no such thing as “I don’t want”: the command arrived – “yes, that’s right”, and left. Moreover, we were summoned to the draft board by urgent alarm. Previously, there was such a tab in the military card, where it was noted that I should be at the place of deployment in 6 hours. Nobody said anything about the accident. Just in those days, the World Cycle Race took place in Kiev. We overheard from the edge of my ear that an accident had occurred, nothing more.

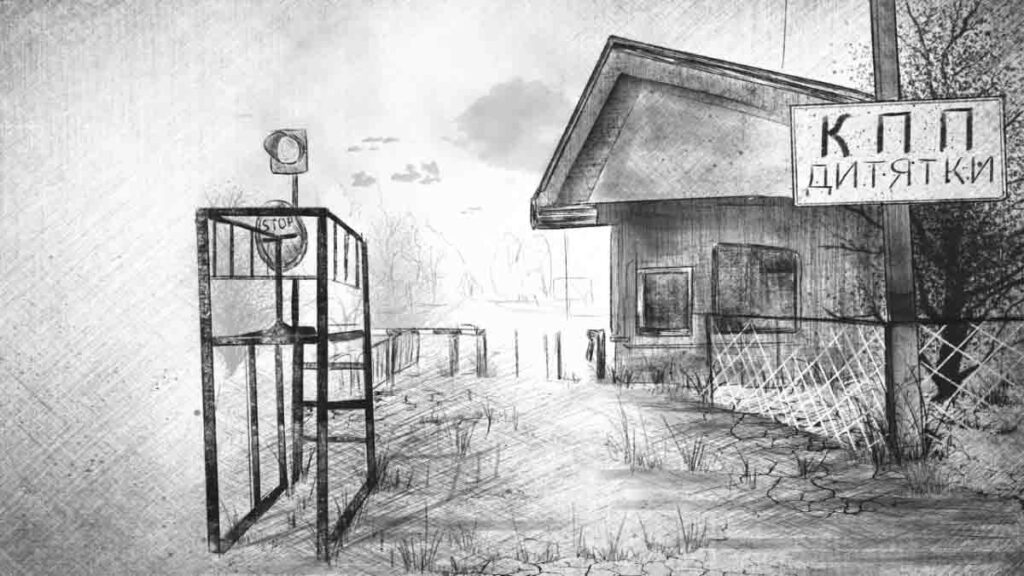

When I arrived at the draft board, they told me that they were summoning as a reserve officer for retraining. We really didn’t know that we were going to Chernobyl. When we arrived in Bila Tserkva, only the head of the special department appeared before us and said that we were going to save Ukraine from the atomic plague. They said to me: “You are an officer, take the company.” I took a company of guys like me who just served in the army. I was 26 years old. This was the beginning of August 1986. I arranged the guys and we went. When we stopped at Chernobyl, it was scary. There was nothing around, not a soul.

Upon arrival at the place of deployment, a representative of the military prosecutor’s office appeared before us and said: “If someone does not follow orders, we will judge you by the law of wartime.” Then we quickly realized what radiation was.

We got up at 4 a.m. every morning. We had breakfast in a quick way, and then departure to the reactor. The first time we were told: “Today your task is to carry out decontamination in the engine room.” There is a dosimetric, I follow him: we check the level of radiation whether people can work there, or not.

“There were places where you cannot approach at all, not just a meter, but 100 kilometers!”

The dosimetrist had a large dosimeter. We were given small, wearable ones, and when we began to check the level of radiation from them, they went out of order before our eyes. Each shift for 20 minutes with rubber soda mixed with water tore out everything at the reactor and in the engine room: apparatus, equipment, walls. Then, shower and rest until the next morning, because if the sun shines strongly, then it was impossible to work. It was very large radiation, people literally fell.

It was certainly hell

The worst thing was when graphite was dropped from the roof of the 4-th reactor. I climbed onto the roof and the first thing I saw was a Japanese robot, similar to the Vladimirimets tractor. The robot jammed and it stopped working. Then, ours from a helicopter lowered a conventional tractor onto the roof of the engine room and started it from the control panel. They couldn’t manage it either, but they cannot turn it off. It just fell into the crevice.

Before we climbed onto the roof of the reactor, we were changed clothes, put on lead gowns, and underneath were tunics soaked in some kind of brown muck. They worked like this: you go out onto the roof, drop one or two shovels of graphite and return. This should have taken 40 seconds, then the next soldier followed the same pattern. Each worked for 40 seconds, then we take off all the clothes, wash and go to the place of deployment. Of course, it was hell. There was a constant release from the reactor – a two-kilometer uranium rod, infecting everything around 200 years ahead. There was continuous radiation all around. But we, young guys, did not know what it was.

There were many unusual situations. For example, we checked villages whose population was evacuated. Everything remained in the village of Kopachi, where we arrived with a company: motorcycles, cars, houses with all the acquired property, food in the fridges. However, there were no people.

Once a goose was attached to our company, its own. We found it in Kopachi. So the guys first wanted to eat it, and then changed their minds. He even followed us to company formations. Everyone got used to him, and the battalion commander and regiment commander believed that he was a member of our team. Many animals remained there, in the village. A special team fired pigs, and then exported them.

There were a lot of chickens, homeless dogs, cats. Then, the people who were taken to the evacuation, no one allowed to take animals with them. They took only documents and money. People fled to their relatives, some to Kiev, some to Poltava, many to Belarus. And everything acquired over the years was left, even cars, motorcycles. This was scary: empty cities, abandoned villages!

An old woman lived in Kopachi who refused to leave, and at the sight of the soldiers she was constantly hiding, as in the Patriotic War, from the Germans, so that we would not pick her up and take her away. Not many, but there were such families, mostly elderly people, who said that their parents’ graves are here, and they will not go anywhere.

They were forcibly taken out, but they ran away, returned, hid and lived … We, the liquidators, simply fulfilled our duty, as a result of which many became disabled. But I will never kneel down or ask to be given a hand … This has never been and never will be. Chernobyl changed my life… “

These are the memories left by the liquidators who visited the Chernobyl hell. Sometimes, their character is harsh – the accident hardened. Having passed through ordeals, by strength of mind, firmness, integrity, and, if you like, patriotism, they look like that old woman who, it seems, will not be scared even by the plague epidemic and will not leave her home. What kind of radiation is there? Home and native land are her fortress, her wise philosophy of life.