It would seem that not a single disaster in the world is talked about as much as a disaster at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. Sometimes the information offered is not always true, separate myths about the accident exist to this day.

We drew a parallel between the official data and the story of Sergei Mirny, the liquidator of the accident, the platoon commander of the Chernobyl radiation intelligence. He is a lump man who devoted his whole life after the accident to study its consequences.

Returning to his laboratory after the accident, he first continued to work on physical and chemical research, and then devoted his life to eliminating information pollution, which after the Chernobyl disaster began to take shape in society. He is not just a liquidator, he is a direct witness to events.

Today, working as the chief guide of the Chernobyl Tour organization, he debunks the senseless Chernobyl myths that some still believe in, clarifies the truth about the real consequences of the disaster, which many do not even think about.

The Chernobyl expert interview

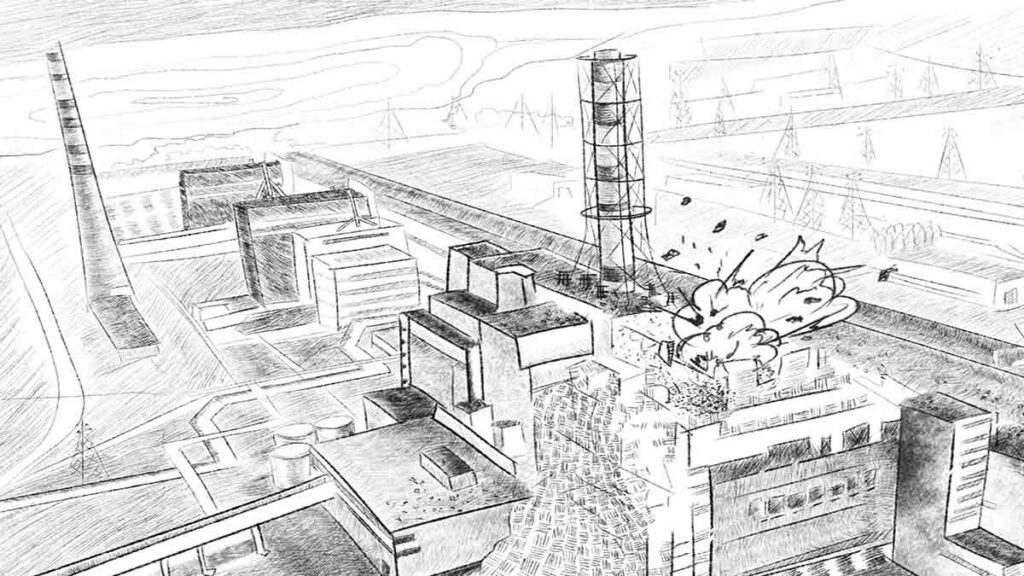

Officially: on April 26, 1986, an explosion occurred at the fourth power unit of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, which completely destroyed the reactor. The so-called active stage lasted 10 days. There were intense releases of radioactive elements all this time. Among other things, isotopes of uranium, plutonium, iodine – 131, iodine – 134, cesium – 137, strontium -190. The first days, a blazing flame rose above the ruins of the reactor to a height of more than a kilometer, a little later rose several hundred meters.

Sergey’s comment: The most dangerous level of radiation actually covers slightly smaller territories. The heavier the particles of nuclear fuel, the closer they will fall. The lower the level of pollution, the more uniform it is and the larger the area it occupies.

Question: In the process of acquaintance with some memories, one gets the impression that the heroism and desire of ordinary liquidators to do something constantly came across some kind of idiocy in the face of individual staff officers. How did everything look in practice?

Comment: This is often true. Having arrived at Chernobyl at the age of 27, I saw a typical Soviet system in its best traditions. It`s a colossal opportunity to mobilize a gigantic resource thrown into liquidation, and at the same time, its equally colossal inefficiency.

The lion’s share of the effort was spent not on combating the consequences of the accident, but on combating departments. I am a radiation scout, my task, moving through the most polluted territory, is to conduct a column of armored reconnaissance and patrol vehicles in the Zone, get a mission at headquarters, distribute it, send all crews on routes, and go on reconnaissance myself.

In the evening, I should hand over the accumulated material to the headquarters, and at night in the camp to process mountains of documents, reports, analyzes, make plans for the next day, paint routes for the movement of equipment, prepare analytics for management. A lot of pointlessly spent time and nerves, against this background, I was occupied with communication with deactivators.

The system was organized primitively. It would seem that everyone is doing his job. But the intelligence team has its own nuances of work, which did not always fit in with the requirements and standards of those services that dealt with. It simply wasn’t possible to “wash” us normally – neither people nor cars could give in to 100% treatment with decontaminants.

Every day we walked along the edge of a knife; reconnaissance is a dangerous mission. The information we obtained was secret, it was immediately sent to the operational headquarters of the Zone for transmission to the radiation intelligence department at the USSR Ministry of Defense. We had the most complete, accurate, and reliable information about the radiation situation.

Everything that we discovered was used by nuclear scientists to prepare reports in the government commission. We worked in the most infected places. The increased radiation background of special equipment could not be washed up in any way in order to bring deactivators to standards.

My platoon to the platform for sludge equipment, the so-called “burial ground” – was sent almost every day. In roundabout ways, we still circumvented the zone, since I simply had no right to leave the special equipment with radiation equipment without proper supervision, what kind of “repository” could be discussed?

Question: Did the command understand what they had to deal with, and what was radiation?

Comment: It is difficult to answer unequivocally. The Chernobyl disaster was an absolute surprise for everyone – we all studied there, all gained experience. I would not put the blame on anyone specifically. But it is also impossible to ignore the fact that there was a delay with conclusions and decisions that needed to be promptly taken at the first stages at the leadership level.

Obviously, no one could finally believe in the enormous scale of the accident and foresee its consequences. It is ridiculous to recall that on the third day after the incident, the deputy energy minister cheerfully reported to management that three months later the fourth power unit, which no longer existed, was again connected to the unified energy system of the USSR.

Question: What are the real medical consequences of Chernobyl?

Comment: There are two types of consequences that are completely related to the exposure factor.

The first one: there are several hundred deaths from acute radiation sickness among those who were originally at the station at the time of the disaster and those liquidators who started work in the first hours and days after the accident. I do not really trust the existing statistics, but even if it is reduced several times, then we are talking about several thousand people. These are creepy numbers, actually. They only seem to be a small percentage against the background of the total number of liquidators, measured in the amount of 600-900 thousand.

The second one: Polesie is an iodine-deficient region, radically different, for example, from the Azov or Black Sea coast, in which everything is in order with iodine. The thyroid gland of the inhabitants of Polesie eagerly absorbs all the iodine that enters the body. The most greedy in this sense is the thyroid gland of children.

It takes part in the growth processes, therefore, it is extremely important for the growing body of the child. And then an accident occurs, as a result of which the fourth reactor explodes. In it, in addition to everything else, radioactive iodine is accumulated, the product of the decay of nuclear fuel. It is carried with terrible force throughout the Polessye region.

Locals, especially children, absorb it like a sponge in water. The thyroid gland is irradiated, concentrating its maximum amount in itself. Before the accident, thyroid cancer in local children was an extremely rare type of disease, 2-3 cases per 100 thousand children. After, it increased approximately 100 times.